Four Gentlemen of Spice

Published:

2025-04-29

You won’t find any fish in Yuxiang Rousi (Fish-Fragrant Shredded Pork)—its flavor comes not from seafood, but from a well-balanced combination of pickled chili peppers, Sichuan salt, soy sauce, sugar, minced ginger, garlic, and shredded scallions.

Unlocking the Secrets of the Four Spicy Staples: Chili, Ginger, Garlic, and Scallions

Often referred to as the “Four Gentlemen of Spice,” chili, ginger, garlic, and scallions each bring their own unique contribution to the kitchen. In modern cooking, they’re more than just condiments—they shape the taste, aroma, and character of countless dishes.

Spiciness, although not a basic taste like sweet or salty, is a powerful sensory experience. A touch of heat can awaken the palate, cut through richness, and elevate the complexity of a dish. Each of these four ingredients offers a different interpretation of “spicy,” enriching the way we experience flavor.

The “Four Gentlemen of Spiciness”-Chili,Ginger, Garlic, and Scallion

01. Fiery Chili Peppers: Heat That Hurts So Good

Although we often lump “spicy” in with the five basic tastes, it’s not technically a taste at all. Instead, the burning sensation you feel when eating chili comes from capsaicin—a compound that triggers the pain receptors in your mouth and skin. In short, spicy is a kind of “pain,” not flavor.

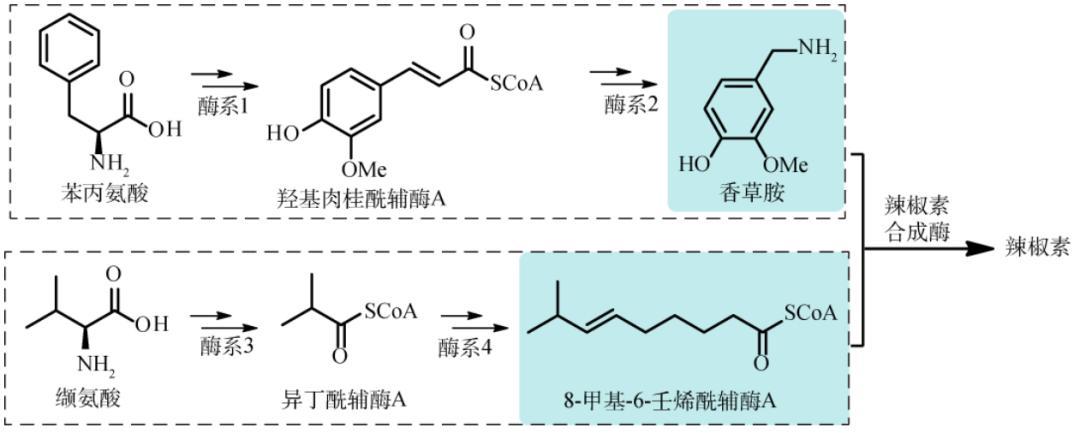

The heat in chili peppers is due to a group of alkaloids known collectively as capsaicinoids. There are five primary types: capsaicin, dihydrocapsaicin, nordihydrocapsaicin, homocapsaicin, and homodihydrocapsaicin. Of these, capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin are the heavy hitters, accounting for about 90% of the total and delivering the majority of the pepper’s pungency.

Biosynthesis pathway of capsaicinoids

In Chinese cuisine, especially Sichuan dishes, chili peppers are indispensable. Varieties like Erjingtiao, Zidan Tou (Bullet Head), and Qixing Jiao (Seven Star Chili) are essential for creating flavor profiles ranging from home-style spicy to numbing-hot and aromatic.

Take Yuxiang Rousi for example again—there’s no fish in sight, but thanks to a precise balance of salty, sweet, sour, spicy, and umami, the dish achieves a “fish-fragrant” profile that’s complex, layered, and deeply satisfying.

02. Ginger: A Classic Companion for Fish. Old and Bold.

Ginger is an essential spice in Chinese cuisine, valued not only as a flavoring agent but also as a vegetable and a traditional medicinal herb. Its distinctive sharpness and aroma permeate dishes, enhancing their overall freshness and appeal.

There’s a saying in Chinese kitchens: “Fish goes with ginger, meat goes with sauce.” goes a Chinese culinary saying. That’s because ginger has the ability to neutralize unpleasant fishy or gamey odors, making it a staple in home kitchens.

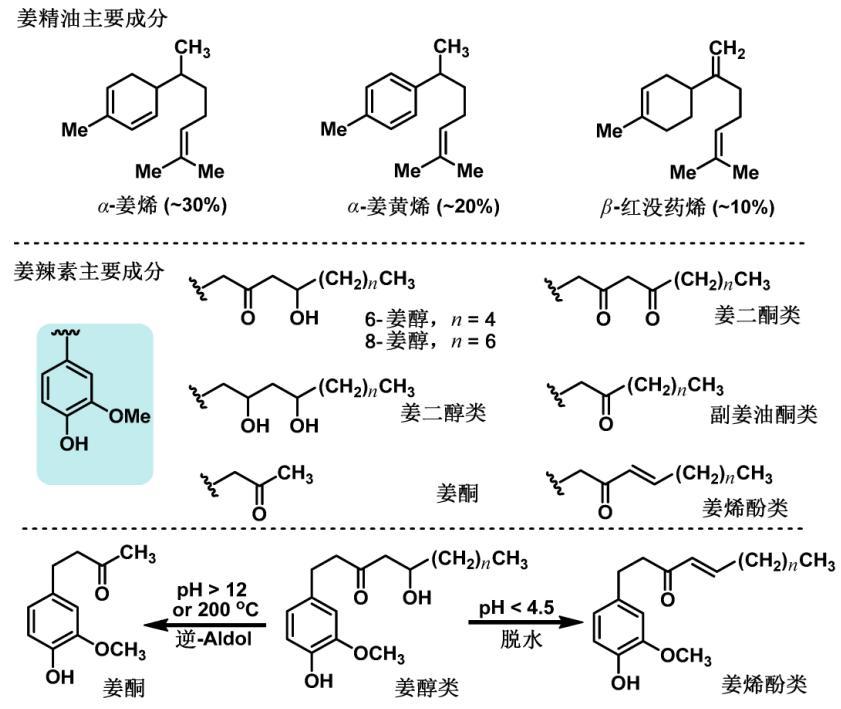

The sharp, clean heat of ginger comes mainly from compounds like gingerol and shogaol. These are volatile aromatic substances, meaning they not only add heat but also stimulate both the mouth and the nose when eaten.

Flavor compounds in ginger and their interconversion

Studies have shown that these spicy compounds benefits the human body by producing antioxidant enzymes to combat free radicals, contributing to anti-aging effects. Ginger also has antibacterial properties, with particularly notable effectiveness against Salmonella.

One common myth, however, is the saying “rotten ginger doesn’t rot its flavor.” In truth, spoiled ginger can produce a compound called safrole, which is potentially toxic and harmful to the liver. For safe and delicious dishes, always use fresh, firm ginger.

03. Garlic: Silent But Sharp

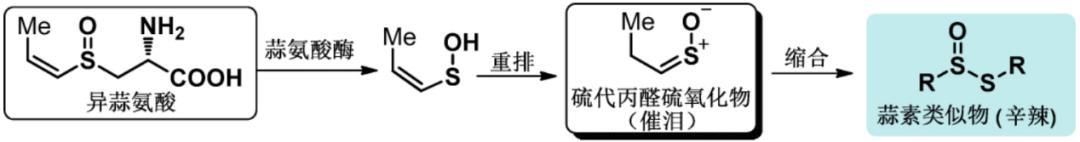

Garlic is a kitchen essential across cultures, prized for its ability to boost flavor and kill off odors—particularly in raw or cold dishes. But here’s a fun fact: whole garlic cloves don’t actually smell.

Garlic is a kitchen essential across cultures, prized for its ability to boost flavor and kill off odors—particularly in raw or cold dishes. But here’s a fun fact: whole garlic cloves don’t actually smell.

Allicin is unstable and quickly breaks down into other sulfur-rich compounds, such as diallyl disulfide, trisulfide, and tetrasulfide. Among these, diallyl trisulfide—often referred to as “garlic oil” in official pharmacopeia—packs the strongest antibacterial punch.

Source and transformation of pungent compounds in garlic

Interestingly, allicin is sensitive to both heat and salt. When cooked or heavily seasoned, garlic loses much of its potency. That’s why raw garlic is often the most effective when you want that punch of flavor or its health benefits.

04. Scallions: Mild Heat, Big Impact

Scallions (or green onions) are a cornerstone of Chinese cooking—used to start a stir-fry, finish a dish, or add that final aromatic touch. As the saying goes, “No scallion, no stir-fry.” Their presence brings depth and brightness to a meal.

The mild pungency in scallions comes from sulfur compounds like dipropyl disulfide and methyl-propyl disulfide. While not as aggressive as garlic or chili, scallions still deliver a pleasant heat, especially to the nose.

Formation process of pungent compounds in scallions

Different types of scallions have different uses. “Beijing scallions” are thicker and suitable for both raw and cooked applications, while slender “spring onions” shine in seafood dishes or cold salads.

Raw scallions can be quite pungent, but once cooked, their heat mellows and gives way to a subtle sweetness. This transformation is due to heat-induced conversion of sulfur compounds into thiols—molecules known for their mild sweetness and distinctive aroma.

Final Thoughts

Chili, ginger, garlic, and scallions—each carries its own style of heat, aroma, and tradition. Together, they represent a rich, flavorful heritage of Chinese cuisine. Their distinct but complementary characters turn everyday dishes into unforgettable culinary experiences.

Relative news

sales@garlicare.com

sales@garlicare.com

Feedback

Feedback